And why my research is ground-breaking but not publishable

P-hacking - defined as undisclosed analytic flexibility that inflates false-positive findings - has been widely discussed as a contributor to the replication crisis across the behavioural sciences. While often distinguished from outright scientific fraud on the basis of intent, p-hacking produces equivalent epistemic damage by introducing untrustworthy findings into the literature.

Psychiatry is particularly vulnerable to this phenomenon due to the abstract nature of its constructs, the heterogeneity of its phenotypes, and the high dimensionality of its measurement tools. This essay examines why p-hacking is especially prevalent in psychiatric research, explores its specific consequences for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) research, and argues that phenotype-first clinical reasoning - anchored in reproducible functional effects and cross-contextual patterns - offers a partial corrective to literature distortion driven by statistical flexibility.

Over the past decade, concerns about reproducibility have reshaped discourse across psychology and the behavioural sciences. Central to this debate is the recognition that many statistically significant findings fail to replicate, particularly in fields reliant on complex, indirectly measured constructs. One mechanism underlying this failure is p-hacking: the practice of exploiting researcher degrees of freedom in data collection, analysis, or reporting to obtain statistically significant results. Although p-hacking is often framed as an unintentional by-product of flexible research practices rather than deliberate misconduct, its cumulative effect is the systematic contamination of the scientific record.

Psychiatry occupies a distinctive position within this crisis. Unlike many biomedical disciplines, psychiatry relies heavily on latent constructs, self-report instruments, and behaviourally defined syndromes whose boundaries are neither biologically discrete nor temporally stable. This essay argues that these structural features make psychiatric research especially susceptible to p-hacking, with downstream consequences for theory development, genetic interpretation, and clinical translation. ADHD is used as a case study to illustrate how p-hacking has shaped prevailing models in ways that are misaligned with robust clinical patterns, and how phenotype-anchored reasoning may help restore constraint and coherence.

What Is P-Hacking?

P-hacking refers to a range of analytic practices in which researchers, often without explicit intent to deceive, explore multiple analytic pathways and selectively report those that yield statistically significant results. These practices include post hoc selection of outcome variables, subgroup analyses conducted after inspecting the data, flexible inclusion or exclusion criteria, optional stopping of data collection, and selective reporting of models or covariates. Crucially, p-hacking does not require data fabrication or falsification; it operates entirely within the nominal rules of statistical testing while violating their underlying assumptions.

The ethical distinction between p-hacking and fraud is typically drawn on the basis of intent. Fraud involves deliberate misrepresentation, whereas p-hacking often arises from cognitive biases, publication pressures, and methodological norms that tolerate analytic flexibility. However, from the perspective of the scientific record, this distinction is largely irrelevant. Both practices increase the rate of false positives, inflate effect sizes, and undermine the reliability of published findings.

Why Psychiatry Is Especially Vulnerable

Several structural features of psychiatric research amplify vulnerability to p-hacking. First, psychiatric constructs are latent rather than directly observable. Variables such as “attention,” “impulsivity,” “emotional regulation,” or “executive function” are operationalised through questionnaires, behavioural tasks, or composite scores, each of which can be subdivided, recombined, or reframed in multiple ways. This creates a high-dimensional analytic space in which statistically significant associations are likely to emerge by chance alone.

Second, diagnostic categories in psychiatry are heterogeneous and overlapping. Individuals meeting criteria for the same diagnosis may differ substantially in symptom profile, comorbidities, developmental trajectory, and underlying biology. This heterogeneity invites post hoc stratification — by subtype, sex, age of onset, comorbidity, or severity — further expanding researcher degrees of freedom.

Third, effect sizes in psychiatric research are typically small, particularly in behavioural and genetic studies. When true effects are weak, the signal-to-noise ratio is low, and analytic flexibility disproportionately increases the likelihood that noise will be mistaken for signal. Over time, this produces a literature populated by fragile findings that are difficult to replicate but difficult to falsify.

Fourth, theory in psychiatry is often under-constrained by biology. In the absence of strong mechanistic anchors, statistically significant associations can be retrofitted into plausible narratives post hoc. This theoretical elasticity allows p-hacked findings to be assimilated rather than challenged, even when they are counter-intuitive or conceptually incoherent.

Built in bias?

Bias is not an aberration in research practice but a structural feature of knowledge production, particularly in academic environments where career progression depends on publication volume, novelty, and statistical significance. P-hacking is therefore best understood not as individual moral failure but as an emergent property of incentive systems that reward positive findings and render null results largely unreadable, unpublishable, and professionally costly.

Researchers are typically drawn to questions they care deeply about, hold prior beliefs on, and hope will yield meaningful effects; expecting investigators to approach questions of no personal or theoretical interest is both unrealistic and antithetical to how science actually advances.

Under such conditions, analytic flexibility becomes almost inevitable: choices about outcomes, subgrouping, covariates, and framing are unconsciously steered toward coherence and significance. That this occurs even among well-intentioned researchers is evidenced by the replication crisis itself. Indeed, given the asymmetry of rewards — where novelty and confirmation are prized, while restraint and null findings are penalised — it is arguably remarkable that any academics consistently resist these pressures.

The appropriate response, therefore, is not moralisation but epistemic humility: acknowledging that bias is ubiquitous, that belief precedes investigation, and that methodological safeguards exist not because researchers are dishonest, but because they are human.

Consequences for ADHD Research

ADHD research exemplifies these dynamics. Over several decades, the literature has produced a wide array of claims regarding the nature of ADHD, including models emphasising motivational deficits, executive dysfunction, inhibitory failure, reward sensitivity, emotional dysregulation, or delay aversion. While each of these constructs has empirical support at some level, their proliferation reflects, in part, the ease with which statistically significant effects can be generated within flexible analytic frameworks.

One consequence has been a tendency to prioritise questionnaire-derived constructs over stable functional outcomes. For example, improvements associated with stimulant medication have often been framed in terms of behavioural control or reduced impulsivity, while more robust and clinically salient effects — such as improvements in language processing, reading-to-writing translation, and sustained auditory attention — have been under-theorised. This imbalance reflects the influence of p-hacked behavioural paradigms that favour easily measured but weakly grounded outcomes.

In psychiatric genetics, these problems are compounded. Genome-wide association studies achieve statistical rigour at the level of genotype–phenotype correlation, but the phenotypes themselves are frequently broad, heterogeneous, and defined by p-hacked behavioural literature. Weak genetic signals are then interpreted through the lens of these constructs, generating speculative narratives about personality, cognition, or behaviour that exceed what the data can support.

What about bypassing the system?

It is increasingly difficult to ignore the extent to which the contemporary publication ecosystem itself is compromised, not primarily by bad actors but by structural incentives, gatekeeping norms, and methodological fashions that privilege formal legitimacy over epistemic usefulness. Within this environment, one paradoxical marker of intellectual hygiene may be not attempting to publish at all.

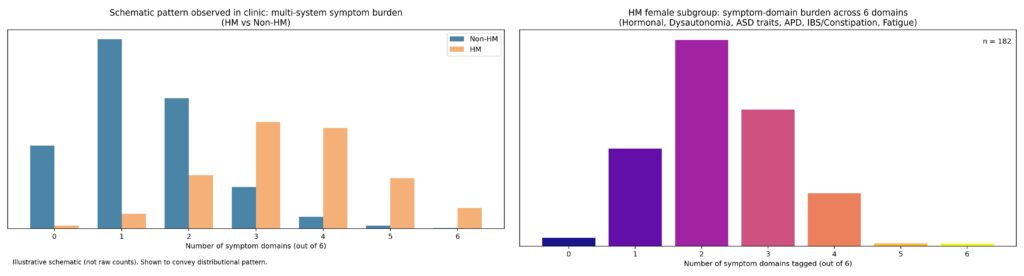

In clinical medicine — particularly in private practice — patients actively choose to attend, to continue treatment, and to return for review; this longitudinal, voluntary engagement constitutes a stringent and ongoing selection pressure that is rarely acknowledged as a form of evidence. Over seven years running a specialist ADHD consultancy, consistent patterns emerged across a large caseload: reproducible phenotype clusters, striking differences between hypermobile and non-hypermobile patients, and large, clinically obvious treatment effects that generated testable hypotheses and reliably improved patient outcomes.

When I tried to formalise these observations — by systematically reviewing approximately 1,000 cases and comparing physical symptom profiles across phenotypic groups — the signal was strong and internally coherent, yet met with scepticism precisely because it did not align with prevailing narratives. Despite repeated encouragement that “the plural of anecdote is not anecdata,” attempts to collaborate or publish stalled, likely reflecting a combination of distrust in non-institutional data, discomfort with effect sizes that challenge existing models, and ethics and governance structures that — however well-intentioned — function to exclude clinician-led, practice-embedded knowledge generation.

The result is an ironic impasse: a clinic with near-universal functional improvement cannot easily transmit its accumulated expertise to colleagues, while the literature continues to recycle smaller, more publishable effects. Accepting this constraint does not entail rejecting science; rather, it acknowledges that in certain domains, treating patients well and letting outcomes guide ongoing practice may be a more reliable epistemic anchor than forcing clinically grounded insight through a publication system ill-equipped to receive it.

Clearly not a team player

Critique of institutional systems by insiders is rarely interpreted as neutral inquiry; it is more often read as a signal of unreliability, deviance, or insufficient professional socialisation. Within medicine and academia, credibility is not conferred solely by technical competence or outcomes, but by perceived membership of an epistemic and moral in-group — by knowing what can be said, how it can be said, and when silence is expected.

Clinicians who question prevailing frameworks, emphasise effect sizes that are “too large,” or prioritise patient-level functional outcomes over sanctioned metrics are frequently treated as anomalous rather than informative. This is not because their observations are demonstrably false, but because they do not conform to the tacit norms that regulate professional discourse.

The sociology of professions has long recognised this process as one of ideological discipline rather than knowledge production: professionals are selected, trained, and retained not only for competence, but for their ability to extrapolate the system’s assumptions into new contexts without challenging them. Those who do not reliably perform this function — often including neurodivergent clinicians, literal thinkers, or “truth-tellers” insufficiently attuned to hierarchy — are marked as risky, regardless of clinical effectiveness.

For clinicians like myself with ADHD and related neurodivergent profiles, this dynamic is often experienced viscerally and early. Many report a lifelong pattern of institutional punishment for excessive honesty, pattern-recognition that outpaces accepted narratives, or failure to intuit when critique must be softened, deferred, or withheld entirely. In this context, advising patients to use stimulant medication strategically in professional settings is not merely about attention or productivity, but about enabling participation without self-sabotage: dampening the impulse to name incoherence, challenge authority prematurely, or insist on truths that the system is not prepared to hear.

The same logic applies to clinician knowledge-sharing. Years of successful private clinical practice — characterised by voluntary patient return, longitudinal engagement, and consistent functional improvement — can generate robust hypotheses and internally coherent patterns, yet remain epistemically marginal because they arise outside institutional pipelines of legitimacy. Attempts to translate such knowledge into publishable form are often blocked not by identifiable methodological flaws, but by governance and ethics structures designed to privilege insiders and suppress unsanctioned epistemic routes.

Professions train conformity…

These dynamics have been examined explicitly outside the medical literature, most notably in Jeff Schmidt’s book Disciplined Minds: A Critical Look at Salaried Professionals and the Soul-Battering System that Shapes their Lives. Schmidt argues that professional education and employment systems do not primarily select for intellectual independence or truth-seeking, but for ideological reliability: the capacity to apply sanctioned frameworks to new situations without challenging their underlying assumptions. Through mechanisms such as examinations, credentialing, peer review, and informal reputational signalling, professionals are trained in what Schmidt terms “assignable curiosity” — learning not only how to solve problems, but which questions are permitted to be asked.

Crucially, dissent is rarely punished on technical grounds; rather, those who challenge institutional narratives are framed as unprofessional, unbalanced, or insufficiently rigorous, even when their work is competent and their outcomes strong. Although Schmidt’s analysis is not specific to medicine, it maps closely onto contemporary academic psychiatry, where clinicians who foreground clinical effect sizes, phenotype coherence, or system-level critique may find themselves marginalised — not because their observations are incoherent, but because they fail to reproduce the epistemic discipline required for institutional trust.

The result makes it very hard to succeed if you question the system. Clinically effective knowledge remains siloed, while the system rewards smaller, more orthodox effects that preserve consensus. Recognising this does not entail paranoia or rejection of science; it reflects an understanding, learned through repeated cost, that modern professional systems punish those who are “not one of us,” even — and sometimes especially — when they are right. And much as I love my colleagues, it’s why these days I work alone, managing my own private clinic.

Did I p-hack my own data?

Although this work may superficially resemble p-hacked research when viewed through a narrow methodological lens — being retrospective, non-pre-registered, and exploratory in nature — it does not meet the substantive criteria for p-hacking. P-hacking refers to the undisclosed optimisation of analytic choices in order to obtain statistically significant results within a hypothesis-testing framework.

By contrast, the analyses undertaken here were descriptive and hypothesis-generating, designed to characterise phenotypic patterns that had already emerged consistently and repeatedly in clinical practice over many years. The observations preceded the analysis; the numbers were used to estimate magnitude and coherence of an existing signal rather than to discover or manufacture one. No iterative model-searching was undertaken to “achieve significance,” no outcomes were selectively suppressed, and no claim of population-level causal inference was advanced.

Most importantly, validation did not rest on statistical thresholds but on large, reproducible functional effects — changes in symptoms, physiology, and real-world functioning that were clinically obvious, mechanistically plausible, and sustained across contexts. While such work sits outside the conventions of confirmatory academic research, this reflects alignment between method and purpose rather than analytic impropriety: it is phenotype characterisation grounded in clinical effect, not p-hacking driven by statistical convenience. And of course I’m not saying that the observations are complete, universally generalisable, or immune to error, just that they work very well in my clinic, for my patients.

No but it sure might look like it

When viewed through a conventional academic lens, the retrospective data appear almost too strong to be credible: distributions are sharply separated, effect sizes are large, and cluster burden differs dramatically between hypermobile and non-hypermobile groups. In a literature habituated to small, noisy effects, such clarity paradoxically triggers distrust.

Because the analyses were retrospective, non-pre-registered, and clinician-generated, they are readily dismissed as artefactual, despite their internal coherence and clinical plausibility. Yet this reaction reflects a methodological inversion: the data are not implausible because the signal is weak, but because it is strong. Modern psychiatric research has been conditioned by decades of p-hacked, underpowered studies to expect subtle, ambiguous differences that require extensive statistical scaffolding to justify.

In that context, a clean separation — especially one grounded in phenotype rather than diagnosis — violates expectations and is reclassified as suspect. The irony is that these figures represent precisely what clinicians are trained to look for in practice: large, repeatable patterns that meaningfully change management and outcomes. Their retrospective nature does not undermine their validity as hypothesis-generating clinical epidemiology; rather, it renders them incompatible with a publication system optimised for incremental, institutionally sanctioned effects.

This is why, despite repeated exhortations to “publish the data,” such work cannot easily pass through formal channels without being stripped of its most informative features. Still glad I did it, but from now on I’m sticking to the clinic…

Phenotype-First Clinical Reasoning as a Corrective?

P-hacking represents a structural vulnerability in modern psychiatric research, arising not from individual malfeasance but from the interaction of flexible methods, abstract constructs, and publication incentives. Its effects extend beyond false positives to shape theory, obscure robust clinical signals, and complicate the interpretation of genetic data. ADHD research illustrates how these dynamics can delay recognition of stable, clinically obvious patterns in favour of statistically convenient but conceptually diffuse models.

Phenotype-first clinical reasoning offers a partial antidote to these distortions. Unlike post hoc statistical inference, clinical pattern recognition is anchored in repeatability, effect size, and cross-contextual consistency. When a treatment produces large, reliable functional changes across diverse individuals and settings — such as consistent improvements in language processing with stimulant medication — this constitutes a form of evidence that is robust to p-hacking, even if it is not initially captured by formal trials.

This approach does not reject statistical methods but re-orders their role. Rather than allowing flexible analyses to generate theory, phenotype-first reasoning uses stable clinical patterns to constrain interpretation. Genetics and behavioural measures are then deployed directionally, to refine understanding within these constraints rather than to generate unconstrained narratives.

Caveat Lector

Or let the reader beware. Across domains where status, power, or prestige distort incentives, trustworthiness often correlates inversely with desire. We are wary of leaders who hunger for authority, players who prioritise winning over the game, and judges who seek applause rather than justice. Science is no exception.

When publication, citation, and novelty function as professional currency, the desire to publish ceases to be epistemically neutral. It bends questions, methods, and interpretations toward what is legible, fundable, and career-advancing rather than what is durable, replicable, or clinically useful. Under these conditions, scepticism toward unreplicated findings is not cynicism but rational hygiene. The most reliable signals may come instead from those least rewarded by the system: clinicians focused on outcomes rather than authorship, researchers willing to sit with uncertainty, and observers who withhold claims until they survive contact with reality.

This is why the publication ecosystem itself now requires reform, not moral exhortation. A two-tier system — explicitly distinguishing preliminary, unreplicated findings from those that have demonstrated reproducibility and real-world validity — would restore proportional trust without suppressing exploration. Until such alignment exists, a certain irony holds: it may indeed be easier for a camel to pass through the eye of a needle than for an academic system optimised for novelty and prestige to reliably produce clinically transformative, replicable knowledge. That is not an indictment of individual researchers, but of incentives that reward appearance over endurance. Where truth matters, wanting it less loudly may be the first step toward finding it.