What if ADHD is not a disorder, but a mismatch: a brain wired for movement and immediacy operating in a slow, abstract world?

ADHD is often framed as a modern epidemic: an escalating diagnosis driven by school failure, distraction, and digital overload. But what if we have misunderstood its roots? Recent insights from human genetics suggest that ADHD traits may not reflect dysfunction but a different kind of function, shaped by evolutionary needs and now mismatched to the modern environment. In this article, I explore ADHD through the lens of evolutionary biology, cultural ecology, and stimulant pharmacology — offering a clinical reframe that honours both science and lived experience.

Human Evolution Has Accelerated — Not Slowed

In 2007, Hawks et al. published a landmark paper showing that human evolution has dramatically accelerated over the past 10,000 years. This runs counter to the old belief that cultural change buffered us from biological pressures. Instead, agriculture, population expansion, urbanisation, and novel diseases created powerful new selection environments.

In a world of new diets, social norms, and infectious exposures, humans evolved rapidly. Over 7% of our genes show signs of recent positive selection. Many of them affect metabolism, immunity, and brain function.

This sets the stage for a new clinical question: could common neurodevelopmental conditions like ADHD reflect not delay or damage, but divergent adaptation?

ADHD as a Specialised Neurocognitive Variant

Viewed through an ecological lens, ADHD traits — distractibility, novelty-seeking, hyperfocus, rapid response to the environment — are not simply deficits. They may have conferred significant advantages in more mobile, reactive, or fluid societies. In roles like scouting, foraging, tracking, or sudden threat detection, fast-switching attention and sensory sensitivity would be assets.

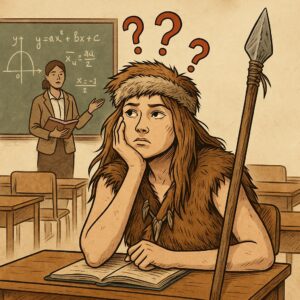

Today, in bureaucratic cultures built around repetition, stillness, linguistic precision, and delayed gratification, these same traits can become liabilities. ADHD is increasingly recognised not as a disease, but as a mismatch: a brain wired for movement and immediacy operating in a slow, abstract world.

Rather than a disorder, ADHD might be better described as a “hunter-specialist phenotype” — one adapted for a different tempo of life. This view echoes the “hunter–farmer hypothesis” popularised by Thom Hartmann, which suggests that traits we now label ADHD may have conferred survival advantages in pre-agrarian societies.

The Role of Language — and Why Medication Helps

In clinical practice, one of the most striking observations is the impact of stimulant medication on language function. ADHD patients often describe profound difficulty with verbal organisation, especially under pressure. They may follow only part of a conversation, lose track of verbal instructions, or struggle to write coherent essays, coursework or session notes despite high intelligence.

Yet with stimulant medication, many patients report a near-immediate shift: language becomes accessible, sequencing improves, thoughts form more clearly. In neurotypical individuals, speech and verbal reasoning are prefrontal tasks. In ADHD, they may rely on effortful backchannels and hyperfocus to compensate.

If ADHD reflects a cognitive system shaped for high-signal environments and low-verbal settings, then modern tasks that depend on sustained verbal fluency represent an evolutionary mismatch. Stimulants act not as cognitive enhancers but as translational tools, enabling access to the language-dominant settings of modern work and education.

Clinical Reframing: Implications for Practice

This perspective has real implications. It allows us to reframe treatment, not as “fixing disorder” but as supporting difference. It justifies the use of stimulant medication not for behavioural control but for unlocking access to communication, autonomy, and participation.

It also invites us to go beyond deficit models when reporting on ADHD in genetic, developmental, or functional assessments. We can highlight areas of natural strength (spatial processing, sensory detail, intuitive problem solving) alongside environmental barriers.

For GPs, therapists, and educators, the task becomes not normalisation, but adaptation: understanding how a fast brain can survive and thrive in a slow world.

Conclusion

If evolution has shaped us unevenly, then neurodiversity is not pathology but a record of that shaping. ADHD may reflect one such branch — a recent, rapid adaptation to high-change environments that now struggles under institutional pressure.

In clinic, this reframe matters. It changes how we explain ADHD to patients. It clarifies why treatment works. And it restores dignity to a condition too often described in terms of lack.

We are not treating broken minds. We are supporting variant minds — tuned for speed, scanning for signals, and still catching up with the world they helped shape.

References

Hawks, J., Wang, E. T., Cochran, G. M., Harpending, H. C., & Moyzis, R. K. (2007). Recent acceleration of human adaptive evolution. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 104(52), 20753–20758

Hartmann, T. (2016). ADHD: A Hunter in a Farmer’s World. Underwood Books – A conceptual exploration of ADHD as an evolutionarily adaptive cognitive style suited to pre-agrarian environments — the “hunter–farmer hypothesis.”